Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

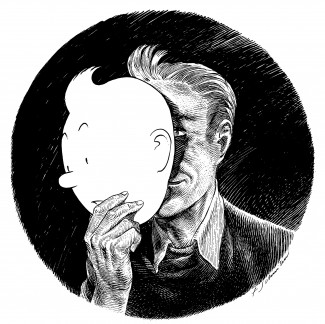

Q&A with Tintinologist Benoît Peeters

Q. Did you know Hergé

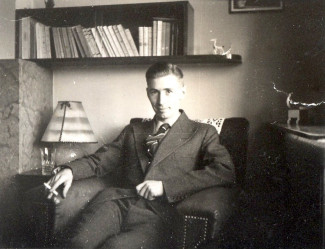

A. I knew Hergé a little in the last years of his life. My first meeting with him dates back to April 29, 1977, when Patrice Hamel and I interviewed him. He spent more than two hours answering all the exacting and bothersome questions—often naive and sometimes downright impertinent—that we asked him. I remember his ready availability, his curiosity about us, his bursts of laughter. I went on to write an analysis of The Castafiore Emerald, volume 21 of The Adventures of Tintin (which would later appear under the title Lire Tintin, les Bijoux ravis), and I thought that was the end of my involvement with Hergé. But he then offered my name to a Scandinavian publisher to write a comprehensive book about his work, which eventually became Tintin and the World of Hergé: An Illustrated History (Le Monde d’Hergé). It was for this book that he gave me what would be his last interview on December 15, 1982.

Q. What did you learn about Hergé while writing your book?

A. The most important discovery I made was that he was a much more complex individual than I had first imagined. Rarely had there been such a gap between the grandeur of a body of work and the colorlessness of its author. The public Hergé, the person of interviews, was frequently wearisome in his sincerity and boy-scoutness. Smooth, almost absent, he seemed to disappear behind his characters. But under it all, there was another Hergé. That Hergé, not always likeable, often hard, and frequently tormented, seemed passionate in a different way.

Q.Was Hergé involved at all in Steven Spielberg’s movie?

Q. What do you think of the movie?

A. Though it’s not my kind of film, I find it honest and think they have succeeded in their own way. In making this film, Spielberg has given a gift to Hergé, whose work is partly cut off from new generations. And overall, he has succeeded. It is obvious that Spielberg has a sincere admiration for Hergé and a real desire to make the movie an homage to him. One can certainly criticize Spielberg for sometimes substituting frenetic activity for meaningful action. But he has to live within the demands of making movies for teenagers in a country that is not that familiar with Tintin. There is in the film some of the brilliance known to all readers of Hergé—for example, Spielberg’s treatment of the tale of Captain Haddock's ancestor. This passage embodies the whole art of comic strips. It's beautifully done, and would have delighted Hergé.