Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Downward Mobility - Q&A with author Katherine Binhammer

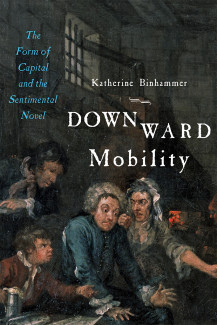

Katherine Binhammer answers questions about her new book Downward Mobility: The Form of Capital and the Sentimental Novel.

Your book on downward mobility in eighteenth-century literature was published right before a pandemic-induced recession. How might British cultural history illuminate the present?

Downward mobility, where a person’s income is less than their parents, has been increasing since the 1980s yet the story economists have been telling is one of unprecedented financial growth. According to pre-COVID numbers, we had never been wealthier. The pandemic has tragically demonstrated why that story was always a lie, with higher rates of deaths for those in lower incomes while corporate America is given bailouts. Who pays for the risks that global financial capitalism assumes has never been clearer than in this moment. The book’s central argument is that the stories we tell about money are more important to our financial well-being than economic statistics and we need to tell a different story. Eighteenth-century cultural history shows us that the main plot is not upward or downward mobility; the true story is about how wealth is distributed and who pays for the risk.

What got you interested in stories of downward mobility in eighteenth-century novels?

I noticed that almost every sentimental novel I read had a story of a character who was once rich but then became poor. I wanted to explain the popularity of the riches to rags narrative, especially when the period corresponds with the beginning of constant economic growth. Why, when people were ostensibly getting richer, were Britons reading stories of downward mobility? My book answers that question by placing it in the context of the rise of financial speculation and I argue that downward mobility equally functions as a myth within capitalism as upward mobility. Stories of financial failure do not primarily circulate to create sympathy for the losers of capitalism but, in the case of the eighteenth-century novel, they helped people believe that infinite economic growth was possible.

What were some of the most surprising things you learned while writing Downward Mobility?

While I knew that plebeian debtors were imprisoned in the period, I did not know about the political campaign against the law. I was excited to delve into the archives of The Society for the Discharge and Relief of Persons Imprisoned for Small Debts; other philanthropic societies from the time like the Foundling Hospital are very well known, but the first debt relief society is not. From 1772 to 1820, the Society freed 51,250 people from prison by settling their debts. A version of the Society remains active in the U.K. today.

I was also surprised to discover that Virginia Woolf’s great-great-grandfather, James Stephen, was an activist, political writer and central figure in the campaign against imprisonment for debt. He’s a fascinating figure; I describe him, using Occupy Wall Street’s phrase, as the first ‘debt resistor’. He understood before anyone else that financial capitalism enslaves the poor through debt, through dividing the world between those with equity and those without.

How is your history of the novel different from others?

By bringing critical finance studies together with literary history and reading plots of downward mobility, I show how the form of capital is fundamentally a narrative form.

Did you encounter any eye-opening statistics while writing your book?

The financial industries today (banks, insurance, pay-day loans, investment firms) constitute 5% of the GDP but generate 10% of the profit. Where does this ‘more’ wealth come from and who benefits? The myth of downward mobility helps keep the fantasy of infinite economic growth alive.

Would you say, then, that your book debunks the myth of downward mobility?

Yes. It shows how downward mobility is as much a myth of capitalism as upward mobility. While the myth of upward mobility has long been debunked, the myth of downward mobility is rarely talked about outside the context of tragedy. I show how the myth actually hides the social inequities produced by increased financialization.

What is the single most important fact revealed in your book and why is it significant?

Hard to say. My book foregrounds how facts and numbers always require interpretation into a series, that is, into narrative form. If I were pressed, I would start my story with this fact:

Limited liability was first introduced into bankruptcy law in 1706. Whereas before, a person who declared bankruptcy would have forfeited all future income until the debts were paid, after 1706, a person’s assets were liquidated and their debts were fully discharged. In other words, you could go bankrupt and then have a second chance. England introduced limited liability before other European countries and economic historians suggest it may have led to their outpacing other countries in economic growth; merchants risk more when they know they can start with a blank slate. More risk means higher returns, a stock market motto that I see germinating in the novel. But what disappears from the story of financial capital is the cost of risk.

Order Downward Mobility: The Form of Capital and the Sentimental Novel -- published on April 28, 2020 -- at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/downward-mobility

Katherine Binhammer is a professor of English at the University of Alberta. She is the author of Downward Mobility: The Form of Capital and the Sentimental Novel and The Seduction Narrative in Britain, 1747–1800.