Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Scopes at 100: Evolution, Expertise, and America’s Cultural Battlegrounds

This summer marks one hundred years since the 1925 trial of John Scopes in Dayton, Tennessee—a misdemeanor case that improbably became one of the most enduring spectacles in American legal history. Ostensibly about whether a high school biology teacher could be fined for violating a Tennessee statute prohibiting the teaching of evolution, the Scopes trial quickly emerged as a national proxy war over science, religion, education, and democracy itself.

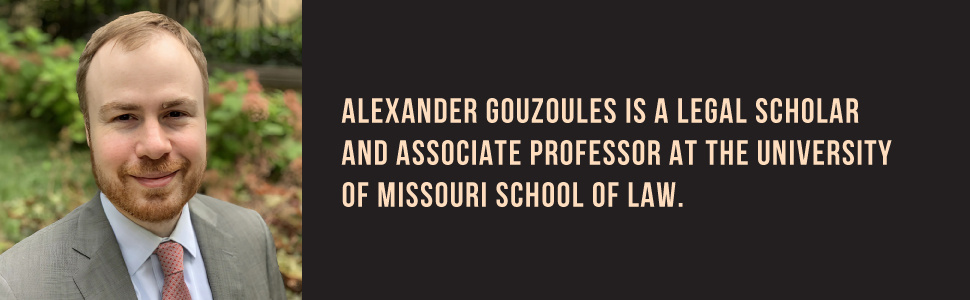

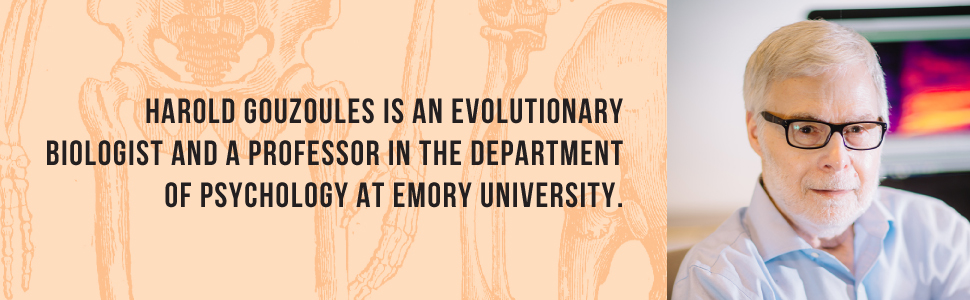

Our book, The Hundred Years’ Trial, revisits this landmark moment with a dual lens: as a constitutional scholar and as an evolutionary biologist, we trace not just the courtroom drama but the century-long legacy that Scopes inaugurated. One of our central arguments is that the trial cannot be understood in isolation, nor should it be relegated to the distant past. Rather, it sits at the intersection of two enduring American struggles: how to reconcile democratic decision-making with scientific expertise, and how to maintain a secular public sphere in a religiously pluralistic society.

These questions are no less urgent today than they were in 1925. If anything, the centennial arrives amid renewed cultural anxiety about what—and whose—knowledge should be taught in public schools. The Supreme Court’s 2025 term concluded with the release of Mahmoud v. Taylor, holding that the religious exercise rights of parents are burdened when their school-age children are exposed to curricular ideas that undermine religious doctrines. Though the case dealt with LGBTQ-inclusive content, its logic extends to controversial scientific ideas like evolution. Indeed, in dissent, Justice Sotomayor warned that evolution might be “next to go.”

Meanwhile, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and escalating climate crises, debates have intensified over the role of expert consensus in shaping public policy. School boards and legislatures across the country have introduced laws targeting instruction on race (e.g., Florida’s HB 7 “Stop WOKE Act,” which limits teaching on systemic racism), gender (e.g., Tennessee’s SB 1229, allowing parents to opt out of lessons on gender identity), environmental science (e.g., Idaho’s 2017–18 legislative removal of references to human-caused climate change from K–12 science standards, and of course, evolution (e.g., recent efforts in Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma to pass 'academic freedom' bills permitting classroom critiques of evolution under the guise of promoting critical thinking).

This new phase of controversy has been sharpened by a dramatic transformation in the Supreme Court’s approach to religion and public life. Not long before Mahmoud, the Court’s decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022) fundamentally retreated from vigorous enforcement of the separation of church and state. That ruling overturned the long-standing Lemon test—first articulated in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971)—which for decades had provided the framework for evaluating government entanglement with religion, including in public education. With that precedent now discarded, the prospect of renewed litigation over the place of evolution in schools is no longer remote.

In these ways and others that we document in the Hundred Years’ Trial, cultural and political tensions that surrounded Scopes have proven remarkably durable. One reason, we suggest, is that evolution poses a unique challenge to popular belief systems. Unlike other scientific concepts that also conflict with literalist readings of scripture—such as heliocentrism or geological time—evolution speaks directly to human identity and purpose. It evokes questions not just of what is true, but of what is meaningful. That was as true for William Jennings Bryan in 1925 as it is for his modern successors.

Another reason for the trial’s enduring resonance is that debates involving science—particularly where they intersect with religion, education, or public policy—have often found their way into American courtrooms. Since the 1960s, evolution instruction has been at the center of a series of landmark cases—Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), and Kitzmiller v. Dover (2005)—though in each instance, courts resolved the disputes primarily through constitutional reasoning rather than scientific adjudication. As we show in The Hundred Years’ Trial, scientific expertise has often played a surprisingly peripheral role in courtroom outcomes. Whether the issue is evolution, climate regulation, vaccine mandates, or reproductive medicine, courts are routinely asked to rule on questions with significant scientific dimensions, but typically do so by evaluating legislative purpose, individual rights, or doctrinal precedent—not by adjudicating scientific validity. In such cases, the courtroom becomes not just a legal forum but a cultural stage, dramatizing public anxieties about expertise, identity, and institutional trust. The trial of John Scopes—complete with a biblical expert on the witness stand and reporters swarming the courthouse lawn—was not the last of its kind. In many ways, it was the first modern example of a trial in which a scientific controversy was symbolically, if not substantively, put on trial.

In The Hundred Years’ Trial, we trace these developments not only through the evolution of constitutional law but also through the intellectual history of evolutionary theory itself—from Darwin to the Modern Synthesis and beyond. As the science has grown more robust and interdisciplinary, the controversies surrounding it have only deepened. Today, misinformation campaigns, legislative interference, and renewed efforts to inject religious doctrine into public education continue to test the boundaries of what science education can and should be.

The centennial of Scopes offers not a moment of closure but a call for reflection. If we fail to reckon with the trial’s long aftermath—its blend of progress and backlash, its courtroom theatrics and constitutional significance—we risk repeating its mistakes. The most enduring lesson of the “monkey trial” may not be about evolution alone, but about the fragility of the institutions we rely on to adjudicate truth in a democratic society.