It’s not easy to write a book on lobbying when lobbyists don’t like to talk about what they do. And it’s particularly difficult when the lobbyists you’re writing about have been dead for one hundred and fifty years. This was the challenge I found myself confronting when I set out to research Lobbyists and the Making of US Tariff Policy, 1816-1861. In researching a previous book on American democratic practices in the early republic, I had become fascinated by fleeting references to lobbyists operating behind the scenes, way-laying Congressmen behind the closed doors of the committee room or in the privacy of their boarding-house parlors. But how to bring these practices out into the open, when by their very nature they were never intended to be made public?

Answering that question involved some old-fashioned detective work. I began by digging through the records of the many meetings and conventions held during the first half of the nineteenth century to express their support either for protectionism or free trade, a debate that was just as divisive then as it is today. These records sometimes contained explicit mention of the appointment of a “delegate” to make their case to Congress, but more often it was a case of cross-referencing the names of those in attendance with other similar assemblies in order to identify the most active individuals in the cause. Then I headed to the archives to track down their surviving papers. Nine times out of ten I would strike out – for the most part, these were not prominent politicians or other public figures, but practical businessmen who left little personal correspondence – but on occasion I got lucky.

One fortunate find was the letters written by Isaac Briggs to his wife during the season he spent in Washington in 1816. Briggs was something of a polymath: he served as secretary to the convention which ratified Georgia’s state constitution, helped survey the boundaries of the District of Columbia, taught school, trained as a printer, tinkered with a design for an early steamboat engine, and finally wound up managing a textile factory in Delaware. It was in the latter capacity that he was chosen by local mill-owners to “communicate with members [of the federal government] on the just & reasonable objects of the manufacturers of this District” with relation to pending tariff legislation. On his arrival in the national capital, Briggs encountered more delegates from elsewhere in the Union entrusted with a similar mission to his own. Together, Briggs recounted to his wife, they decided to “form ourselves into a Society, under a proper organization, have regular and stated meetings, and each one should communicate his ideas to the Society previously to publication elsewhere.” Thus, we might say, was formed Washington’s first ever lobbying agency.

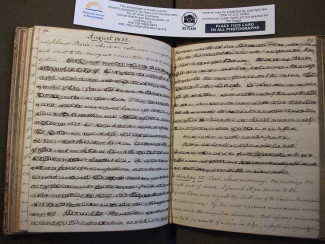

Discovering precisely what lobbyists got up to in the capital was another challenge, when even their employers were keen to remain in the dark. “It is by no means the wish of my colleagues or myself to know the details of any portion of the expenditure, which prudence requires not be divulged, if any such there be,” read the instructions sent to one agent. Once I recall thinking that I had struck gold in the diary of a delegate to the New York Tariff Convention of 1831, which brought together over five hundred protectionist activists from across the Union. The diarist duly recorded the Convention’s proceedings, but when it came to a discussion surrounding the appointment of a lobbying delegation to Washington, the entry had been crossed through.

Evidently, the author had subsequently decided that it was unwise to commit such details to paper! Fortunately, the erasure was effected in a different coloured ink, and I was able, with considerable effort, to make out the entry underneath. What did it say? Well, you’ll either have to decipher it yourself, or read the book to find out…

[image credit: Samuel Breck, entry for 21 August 1832, Volume 5: Diary, 1832-1833, Samuel Breck Papers (Collection 1887), Historical Society of Pennsylvania,

https://hsp.org/. With thanks to the HSP for permission to use this photograph taken by the author.]